WHY DIETING FAILS

Most diets fail because of metabolic adaptation, muscle loss, and hormonal shifts. Discover the physiology nobody explains — and what actually works.

The Physiology Nobody Talks About

A Comprehensive Evidence-Based Review

ABSTRACT

Long-term dieting failure is commonly attributed to poor adherence or insufficient willpower. However, converging evidence from metabolic physiology, endocrinology, and body composition research suggests that biological adaptation plays a central role in weight regain and plateau phenomena. Energy restriction triggers coordinated reductions in resting metabolic rate, non-exercise activity thermogenesis (NEAT), thyroid hormone output, and leptin concentrations, while increasing hunger signaling and reward sensitivity (Rosenbaum & Leibel, 2010; Trexler et al., 2014). Additionally, lean mass loss during aggressive caloric deficits may further depress metabolic rate and predispose individuals to fat regain (Longland et al., 2016). This review examines the physiological mechanisms underlying diet failure, including metabolic adaptation, hormonal modulation, muscle loss feedback loops, and appetite neurobiology. The objective is not to dismiss energy balance principles, but to contextualize them within dynamic biological systems. Sustainable fat loss requires structural alignment with physiology rather than escalating restriction. Understanding these mechanisms reframes dieting failure as a predictable biological response rather than a behavioral flaw.

1. INTRODUCTION: THE PERSISTENCE OF DIET FAILURE

Despite decades of public health campaigns and commercial dieting programs, long-term weight loss maintenance remains rare. Systematic reviews suggest that the majority of individuals who lose weight through conventional dieting regain a substantial portion within 1–5 years (Mann et al., 2007; Anderson et al., 2001).

The dominant narrative attributes this to:

-

Poor compliance

-

Lack of discipline

-

Behavioral relapse

However, this explanation is incomplete.

Energy restriction initiates coordinated physiological responses designed to defend body mass. From an evolutionary standpoint, weight loss signals potential famine. The human organism evolved in environments where caloric scarcity, not abundance, was the primary survival threat.

Thus, when calories decline:

-

Energy expenditure decreases

-

Hunger increases

-

Metabolic efficiency improves

These responses are not pathological. They are adaptive.

The persistence of diet failure is therefore not simply a psychological phenomenon. It is a biological one.

2. DEFINING THE PROBLEM: WEIGHT LOSS VS FAT LOSS VS LEAN MASS LOSS

One of the most critical conceptual errors in dieting discourse is the conflation of weight loss with fat loss.

Body weight consists of:

-

Fat mass

-

Lean body mass (muscle, organs, connective tissue)

-

Glycogen

-

Intracellular and extracellular water

During the initial phase of caloric restriction, glycogen depletion and associated water loss can produce rapid scale reductions. This early decline often reinforces compliance, but it does not represent pure fat reduction.

Hall (2008) demonstrated that changes in body composition during energy restriction are dynamic and influenced by baseline adiposity, protein intake, and energy deficit magnitude. Forbes (2000) further described the non-linear relationship between fat mass and lean mass loss, showing that lean tissue loss increases as individuals become leaner.

This distinction is crucial.

Lean mass is metabolically active tissue. It contributes substantially to resting energy expenditure. Loss of lean mass reduces total daily energy expenditure, thereby narrowing the energy deficit required for continued fat loss.

When dieting protocols fail to prioritize lean mass preservation, they unintentionally undermine long-term metabolic capacity.

Thus, the problem is not merely weight reduction.

It is the composition of that reduction.

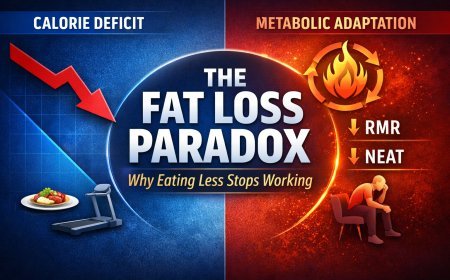

3. METABOLIC ADAPTATION: MECHANISMS AND MAGNITUDE

The concept of metabolic adaptation—also referred to as adaptive thermogenesis—describes the reduction in energy expenditure beyond what would be predicted by changes in body mass alone (Rosenbaum & Leibel, 2010).

In other words:

If a person loses 10 kg, their metabolic rate decreases partly because a smaller body requires fewer calories. However, research shows that metabolic rate often decreases more than predicted by body mass reduction alone.

This additional suppression is adaptive.

3.1 Resting Metabolic Rate Suppression

Resting metabolic rate (RMR) accounts for approximately 60–70% of total daily energy expenditure. During prolonged caloric restriction, RMR declines due to:

-

Reduced organ mass

-

Reduced lean mass

-

Hormonal alterations (particularly thyroid hormones)

Trexler et al. (2014) observed meaningful reductions in metabolic rate among athletes undergoing contest preparation, despite controlled macronutrient intake and resistance training.

3.2 Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis (NEAT)

NEAT includes unconscious movement such as posture shifts, fidgeting, and spontaneous activity. During energy restriction, NEAT often declines significantly—sometimes by several hundred calories per day.

This reduction is rarely perceived consciously.

Individuals may report “doing everything the same,” while their spontaneous movement decreases.

3.3 Thyroid Hormone Modulation

Caloric restriction reduces circulating triiodothyronine (T3), a hormone central to metabolic rate regulation. Even modest reductions in T3 can lower energy expenditure.

This endocrine adaptation further compresses the energy deficit.

3.4 Empirical Evidence: The Biggest Loser Study

Fothergill et al. (2016) followed contestants from a televised weight-loss competition and documented persistent metabolic suppression years after initial weight loss. Participants exhibited resting metabolic rates substantially lower than predicted, even after partial weight regain.

This finding underscores a critical insight:

Metabolic adaptation may persist beyond the active dieting phase.

4. THE MUSCLE LOSS FEEDBACK LOOP

Case Scenario

Mehmet, 34 years old. Lost 11 kilos in 12 weeks.

Diet plan:

Daily deficit of 1,000+ kcal

Cardio 6 days a week

Low protein

No weight training

Initially, he lost weight quickly. A plateau began in week 8. His strength decreased and fatigue increased in week 12.

Six months later, he regained most of the weight he lost — but this time with a higher body fat percentage.

This is not a matter of willpower. This is a physiological chain reaction.

4.1 Why the Body Sacrifices Muscle

Muscle tissue is metabolically expensive.

When the organism perceives an energy shortage:

It wants to increase energy efficiency.

It tends to reduce tissues with high energy cost.

Lean mass, especially if there is no resistance training and protein intake is low, is not a priority for preservation.

Forbes (2000) showed that the rate of lean mass loss increases as fat mass decreases.

Helms et al. (2014) stated that protein requirements increase in calorie deficits.

4.2 Low Protein + High Cardio = Catabolic Bias

The combination of aggressive cardio and low protein:

Reduces muscle protein synthesis

Pushes the net protein balance into a negative state

May increase the cortisol response

Longland et al. (2016) showed that the combination of high protein + resistance training can provide lean mass increase even in an energy deficit.

This means:

Muscle loss is not inevitable. But it requires a protection strategy.

4.3 The Feedback Loop

Lean mass decreases →

Resting metabolic rate decreases →

Total energy expenditure decreases →

The same calorie deficit becomes smaller →

More restrictions are made →

There is a greater risk of muscle loss.

This cycle is the invisible end of most diets.

5. HORMONAL ADAPTATIONS TO ENERGY RESTRICTION

Case Scenario

Ayşe, 29 years old. She remained in a calorie deficit for 16 weeks.

In the last weeks:

Constant hunger

Sensitivity to cold

Menstrual irregularities

Decreased motivation

The diet “wasn’t working.”

But her physiology was working.

5.1 Leptin Suppression

Leptin is secreted from fat cells and reports energy status to the hypothalamus.

Fat loss → leptin decrease →

The brain perceives energy shortage →

Hunger increases, energy expenditure decreases.

Sumithran et al. (2011) showed that leptin levels remain low and hunger hormones increase after weight loss.

5.2 Ghrelin Elevation

Ghrelin is known as the “hunger hormone.”

It increases in energy deficit.

This increase becomes more pronounced as the diet duration lengthens.

This is biological friction. Not willpower.

5.3 Thyroid Axis Suppression

Calorie restriction:

Can reduce T3 levels

Can lower metabolic rate

Rosenbaum & Leibel (2010) detailed the hormonal basis of adaptive thermogenesis.

5.4 Reproductive Hormone Impact

Long-term energy deficit:

Testosterone drop

Estrogen fluctuations

Menstrual irregularities

can be seen especially in aggressive diets.

This is not a signal of sustainability. This is an alarm.

6. APPETITE NEUROBIOLOGY: WHY WILLPOWER IS OVERRATED

Case Scenario

Ali is on his 10th week of dieting. He thinks he can't resist junk food when he sees it at home.

But it's not about willpower.

6.1 Hypothalamic Regulation

The hypothalamus integrates energy signals:

Leptin

Ghrelin

Insulin

Energy status

When there is a calorie deficit, the system switches to "famine mode".

6.2 Dopamine & Reward Sensitivity

Berthoud (2011) demonstrated that energy restriction can affect reward circuits.

During times of famine:

-

High-calorie foods become more appealing.

-

The reward response may increase.

This is an evolutionary advantage.

In the modern environment, it becomes a disadvantage.

6.3 Ultra-Processed Food Amplification

Small & DiFeliceantonio (2019) showed that ultra-processed foods activate the reward system more strongly than natural foods.

Exposure to these types of foods during a diet:

-

It triggers a biological urge.

-

It makes control more difficult.

Again: not willpower, but neurobiology.

So far, the article has made the following clear:

-

Diet failure = metabolic adaptation + muscle loss + hormonal changes + neurobiological stress

-

The explanation of "lack of discipline" is insufficient.

-

7. WHY MOST COMMERCIAL DIETS FAIL STRUCTURALLY

Case Scenario

Daniel, 41, followed a popular 8-week transformation program.

Protocol:

-

40% calorie deficit

-

Two hours of daily cardio

-

Low-fat, low-protein template

-

No resistance training emphasis

Results:

-

Rapid early weight loss

-

Severe fatigue by week 6

-

Plateau by week 8

-

Full regain within 9 months

The issue was not effort.

It was structural design.

7.1 Excessive Energy Deficits

Large caloric deficits (>30–40%) accelerate:

-

Lean mass loss

-

Metabolic suppression

-

Hormonal downregulation

-

Psychological fatigue

While aggressive restriction produces faster short-term scale reductions, it disproportionately increases adaptive thermogenesis and lean tissue loss (Trexler et al., 2014).

Rapid results are marketable.

Physiological sustainability is not.

7.2 Overreliance on Cardiovascular Exercise

High volumes of steady-state cardio without resistance training:

-

Increase energy expenditure acutely

-

But may increase compensatory reductions in NEAT

-

Do not adequately preserve lean mass

Resistance training provides a mechanistic signal for muscle retention during energy restriction (Morton et al., 2018). Without it, the body has little incentive to preserve metabolically costly tissue.

7.3 Insufficient Protein Intake

Many mainstream diet plans fail to adjust protein upward during caloric restriction.

Evidence suggests that protein requirements increase during energy deficits to preserve lean mass, particularly in trained individuals (Helms et al., 2014).

When protein is inadequate, lean mass becomes more vulnerable to catabolism.

7.4 Absence of an Exit Strategy

Perhaps the most overlooked flaw:

Most diets have no reverse phase.

Once the goal weight is achieved, individuals abruptly return to maintenance-level eating patterns. However, metabolic rate may still be suppressed, hunger signaling elevated, and lean mass reduced.

The result:

A physiological environment primed for fat regain.

8. LONG-TERM WEIGHT REGAIN: MECHANISMS OF RELAPSE

Case Scenario

Sara lost 18 kg over 9 months.

Two years later, she had regained 15 kg.She reported:

-

Constant hunger after dieting

-

Reduced energy

-

Lower spontaneous activity

-

Increased food preoccupation

Her experience aligns with documented physiological persistence effects.

8.1 Persistent Metabolic Suppression

Fothergill et al. (2016) demonstrated that metabolic adaptation can persist years after significant weight loss. Participants exhibited resting metabolic rates hundreds of calories lower than predicted.

This persistence suggests that the body may defend against weight loss long after the active dieting phase ends.

8.2 Lean Mass Deficit and Energy Efficiency

Dulloo et al. (2015) proposed that disproportionate lean mass loss during dieting may drive compensatory hyperphagia during refeeding phases.

In simplified terms:

The body attempts to restore lean tissue.

Fat regain may overshoot in the process.This creates a mismatch between body composition and energy intake regulation.

8.3 Elevated Hunger Signaling

Sumithran et al. (2011) showed that increases in hunger hormones following weight loss can persist for at least one year.

Thus, relapse is not merely behavioral.

It is hormonally biased.

8.4 Psychological Restriction Backlash

Chronic restriction may heighten cognitive food preoccupation and increase the risk of binge–restrict cycles.

The combination of:

-

Biological hunger

-

Reduced metabolic rate

-

Environmental food abundance

creates a structurally unstable system.

9. A PHYSIOLOGICALLY INTELLIGENT FAT LOSS FRAMEWORK

If dieting fails due to predictable biological adaptation, then sustainable fat loss must integrate those mechanisms into its design.

The objective shifts from rapid weight loss to metabolic preservation.

9.1 Moderate Energy Deficit (10–20%)

Smaller deficits:

-

Reduce adaptive thermogenesis

-

Preserve lean mass more effectively

-

Improve adherence

Slower progress may paradoxically improve long-term success probability.

9.2 High Protein Intake

During energy restriction:

-

1.6–2.4 g/kg/day may be appropriate depending on training status (Helms et al., 2014)

-

Supports muscle protein synthesis

-

Reduces satiety-related hunger

Protein is not merely a macronutrient.

It is a structural safeguard.

9.3 Resistance Training as Primary Stimulus

Mechanical tension signals muscle retention.

Without this stimulus, caloric restriction defaults toward efficiency.

Resistance training is not optional in a preservation-focused model.

9.4 Strategic Diet Breaks and Refeeds

Intermittent periods at maintenance intake may:

-

Partially restore leptin levels

-

Reduce psychological fatigue

-

Mitigate metabolic suppression

Emerging evidence suggests diet breaks may attenuate adaptive responses, though magnitude varies.

9.5 Sleep and Recovery

Sleep restriction independently alters:

-

Ghrelin

-

Leptin

-

Insulin sensitivity

Energy balance cannot be isolated from recovery status.

9.6 Gradual Reverse Dieting

Instead of abrupt caloric increases:

-

Gradual intake increases

-

Progressive volume normalization

-

Continued resistance training

may reduce rapid fat regain risk.

Maintenance is a phase.

Not an afterthought.

10. CONCLUSION

Dieting Does Not Fail — Design Fails

The prevailing narrative of dieting failure emphasizes personal weakness.

The scientific literature tells a different story.

Energy restriction activates coordinated adaptations:

-

Reduced metabolic rate

-

Hormonal shifts

-

Lean mass vulnerability

-

Heightened reward sensitivity

These mechanisms evolved for survival.

Modern dieting strategies frequently ignore them.

When protocols:

-

Preserve lean mass

-

Moderate the deficit

-

Respect hormonal adaptation

-

Plan for maintenance

long-term outcomes improve.

Sustainable fat loss is not a battle against biology.

It is a negotiation with it.

-

-

REFERENCES

(APA Style – Core Foundational Literature)

Anderson, J. W., Konz, E. C., Frederich, R. C., & Wood, C. L. (2001). Long-term weight-loss maintenance: A meta-analysis of US studies. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 74(5), 579–584.

Berthoud, H. R. (2011). Metabolic and hedonic drives in the neural control of appetite: Who is the boss? Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 21(6), 888–896.

Dulloo, A. G., Jacquet, J., & Montani, J. P. (2015). Pathways from weight fluctuations to metabolic diseases: Focus on body composition changes. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 74(2), 165–175.

Fothergill, E., Guo, J., Howard, L., et al. (2016). Persistent metabolic adaptation 6 years after “The Biggest Loser” competition. Obesity, 24(8), 1612–1619.

Forbes, G. B. (2000). Body fat content influences the body composition response to nutrition and exercise. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 904, 359–365.

Hall, K. D. (2008). What is the required energy deficit per unit weight loss? International Journal of Obesity, 32(3), 573–576.

Helms, E. R., Aragon, A. A., & Fitschen, P. J. (2014). Evidence-based recommendations for natural bodybuilding contest preparation. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 11(1), 20.

Longland, T. M., Oikawa, S. Y., Mitchell, C. J., et al. (2016). Higher compared with lower protein intake reduces lean mass loss during weight loss. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 103(3), 738–746.

Mann, T., Tomiyama, A. J., Westling, E., et al. (2007). Medicare’s search for effective obesity treatments: Diets are not the answer. American Psychologist, 62(3), 220–233.

Morton, R. W., Murphy, K. T., McKellar, S. R., et al. (2018). Protein supplementation and resistance training. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 52(6), 376–384.

Rosenbaum, M., & Leibel, R. L. (2010). Adaptive thermogenesis in humans. International Journal of Obesity, 34, S47–S55.

Small, D. M., & DiFeliceantonio, A. G. (2019). Processed foods and food reward. Science, 363(6425), 346–347.

Sumithran, P., Prendergast, L. A., Delbridge, E., et al. (2011). Long-term persistence of hormonal adaptations to weight loss. The New England Journal of Medicine, 365(17), 1597–1604.

Trexler, E. T., Smith-Ryan, A. E., & Norton, L. E. (2014). Metabolic adaptation to weight loss. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 11(1), 7.

FAQ SECTION

Why do most diets fail long-term?

Most diets fail long-term because energy restriction triggers metabolic adaptation, hormonal changes, lean mass loss, and increased hunger signaling. These biological responses reduce energy expenditure and increase appetite, making sustained weight loss difficult without structural adjustments.

Does metabolic adaptation permanently damage metabolism?

Metabolic adaptation does not permanently “damage” metabolism, but resting metabolic rate can remain suppressed for extended periods after significant weight loss. Recovery depends on lean mass preservation, gradual caloric normalization, and resistance training.

Is slow weight loss better than rapid weight loss?

Moderate, slower weight loss is generally associated with better lean mass preservation and less severe metabolic suppression compared to aggressive caloric restriction.

How can muscle loss during dieting be prevented?

Muscle loss risk can be reduced through:

-

High protein intake

-

Progressive resistance training

-

Moderate energy deficits

-

Adequate recovery

Do hormones like leptin and ghrelin cause weight regain?

Hormonal shifts such as decreased leptin and increased ghrelin after weight loss can increase hunger and reduce energy expenditure, contributing to weight regain if not managed strategically.

INTERNAL LINKING STRATEGY

This article becomes your cornerstone “hub” page.

From this page, you should internally link to:

→ Fat Loss + Muscle Retention Guide

→ Why Most Fat Burners Don’t Work

→ Advanced Amino Formula Review

-

What's Your Reaction?